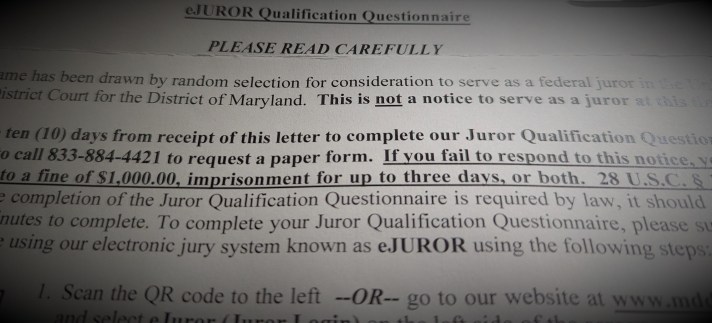

I received a notice the other day from the U.S. District Court in Maryland that I might be called for federal jury duty. It was not a summons, merely a request that I fill out a juror questionnaire. If I do not do as requested, the letter said, “you may be subject to a fine of $1,000, imprisonment for up to three days, or both.” I am inclined, in good citizenship, to comply, but the penalty for not responding adds an extra nudge. Likewise, the possibility of prison or fine, or both, for lying on the eJUROR form is there to keep people from making up phony excuses to get out of federal jury duty.

Like the vast majority of American citizens, I take even the minor laws of the land seriously, including the requirement that I tell the truth when applying for a bank loan. I claim no special virtue; most people take telling the truth seriously, “under penalty of perjury.”

So, given that, let’s look at the Marilyn Mosby mortgage fraud case, playing out in federal court. Mosby is an attorney and the former chief city prosecutor in Baltimore, a position she held for eight years. She’s already been convicted of perjury related to the withdrawal of funds from the city’s Deferred Compensation Plan, claiming that she suffered adverse financial consequences during the pandemic when she was making $247,955.58 a year as Baltimore State’s Attorney.

Her second trial focuses on two alleged acts of perjury — that she failed to disclose a large federal income tax debt on her application for a mortgage on a home in Florida and that she claimed she would “maintain exclusive control” over the eight-bedroom house, despite having ratified a contract with a company to operate her property as a rental.

Mosby’s defense? She blamed her husband for not being truthful about the couple’s tax debt and she blamed her mortgage broker; the broker filled out the loan application forms, she said, and Mosby assumed they were accurate.

Mosby’s defenders says she’s been picked on by federal prosecutors, that none of this is worth an indictment, much less a three-week trial. But I think anyone who has had a mortgage with a bank would agree with two things: (1.) Acknowledging outstanding debt is part of any loan application process and presents a risk of the application being denied, and (2.) you can’t lie about how a house or condo is going to be used; you have to declare if it’s to be a primary residence, a vacation home or a rental property, and those factors make a difference in the financing of a property. Everyone who has come within three feet of a mortgage application knows all this, “under penalty of perjury.”

And that includes people “of ordinary intellect,” to use a phrase one of Mosby’s now-departed defense attorneys employed before her first trial. It was a reference to how a certain phrase or term could not be easily understood or its meaning agreed upon.

Marilyn Mosby is an attorney (Boston College Law School, 2005), and graduates of the nation’s many law schools should know about contracts and perjury better than people “of ordinary intellect.”

Mosby might beat the count regarding the non-disclosure of the federal tax debt. Her former husband, Nick Mosby, the Baltimore City Council president, took the blame for that and it sounds like his lack of candor about the state of the debt led to the breakup of the Mosbys’ marriage. The jury might buy that.

But, if I were a member of said jury, I would likely say, “Come on.” The debt was close to $70,000. It’s hard to believe that both people filing joint returns would not be aware of a problem of that magnitude. Marilyn Mosby never checked the mail before Nick got home from work? She never noticed scaring-looking letters from the IRS? Most of the rest of us — we, the “people of ordinary intellect,” the ones who try to get through this life without a felony conviction — find that unbelievable.

Discover more from Dan Rodricks

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Amen!

But her previous lawyer, with his improper,out of court statements did a pretty good job of convincing a lot of people that the funds improperly withdrawn were “her money“. It didn’t work with the jury, but I work with legal colleagues who bought into it. That was a totally bogus defense. If you have a wealthy uncle who set up in annuity to pay you $100,000 upon your being graduated from college, that money is not yours when you seek it at the end of your sophomore year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Right on, as always.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree! And why such huge places in Florida?!

Rae Eberwine

Bel Air

LikeLike

Unreal

<

div>

Sent from my iPhone

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am one of those ordinary people and know if I sign something, I should have read it and am responsible for its contents being the truth!

LikeLiked by 2 people