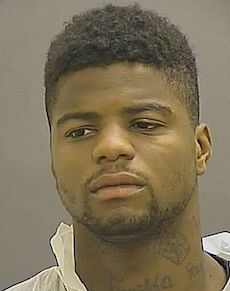

David Warren, the subject of my Sun column — online now, in print on Friday — was sentenced this week to 45 years in federal prison on racketeering charges that involved multiple shootings that resulted in death and pain for several people in Baltimore and Baltimore County. Warren was a hit man for the Black Guerilla Family. My column is about the long vigil for justice held by the family of one of his victims, Bryan McKemy, an innocent bystander killed in Warren’s reign of terror in 2018. Warren, now 32, deserves every bit of that 45-year sentence. Baltimore is much safer with this guy gone. But, for some perspective on this case, please read what I wrote about Warren some five years ago:

DAVID WARREN has to be one of the most successful defendants in recent Maryland history. His record of arrest for crimes of violence is extensive, and yet the state has only a couple of convictions to show for it. In 2019, the law finally caught up to him, but in Baltimore County, not the city, and the jurisdiction of his crime might have made the difference. Warren and his attorney might have decided that, even with circumstantial evidence, a guilty verdict from a jury in the county was more likely than one in the city. Whatever the reasoning, Warren entered guilty pleas to assault and a firearms charge while the state dropped an attempted murder charge. His sentence was 25 years for the assault, with all but 10 suspended, and 5 years concurrent for the gun charge. The judge in the case, the Honorable Robert E. Cahill Jr., did not have much to say about the matter. He merely reviewed the plea agreement, accepted it and imposed sentence. I think, given Warren’s extensive record of contact with law enforcement, the judge might have used the opportunity to admonish the guy, with words to this effect:

Mr. Warren, you won’t be eligible for parole for five years. Please use that time to figure out what you want to be when you grow up. You are 27 years old now, and don’t have much to show for it besides a long record of arrests. To quote a poem by Mary Oliver: ‘What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?’

I heard a judge, Gale E. Rasin, quote that poem to defendants. It’s entirely appropriate for a judge to lecture a repeat offender, and I wonder why more of them don’t take advantage of their authority to do so. When I see a young men at the defendant’s table in court, or in prison, I wonder: Will anyone sit and talk to that guy? Will anyone help to prepare him for a successful return to society? Will anyone even ask what he plans to do with the rest of his wild and precious life?

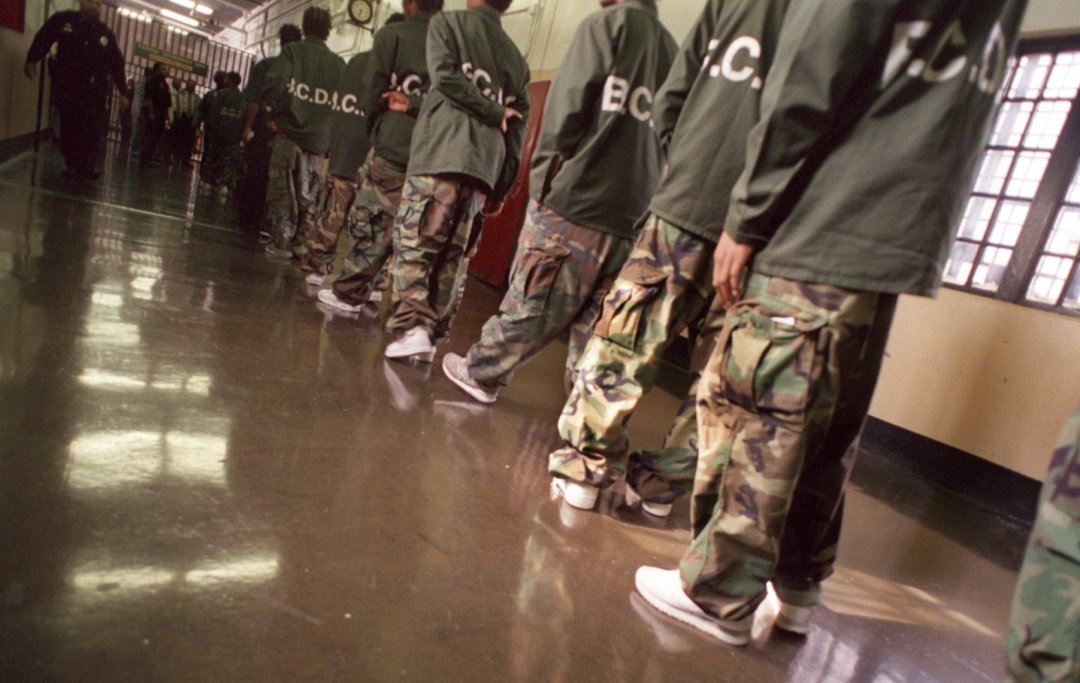

Let’s acknowledge what we’ve learned over the years: The most troubled young men in Baltimore are children of poverty, victims of poor or abusive parenting or no parenting; they failed in school, and many became the easy targets for gang recruitment. By the time they stand before judges for sentencing, it’s either too late to change them — that’s the dark view of it — or there’s little that we offer them in the way of rehabilitation in prison. I believe the latter is the problem: We took correction out of corrections long ago, even before the period of mass incarceration overwhelmed what rehabilitative services state and federal prison systems could offer. I wrote about this, after a teenager in Baltimore County received a life sentence for the death of a police officer. For sure, prison is for punishment. But, given that people like David Warren — in fact, the vast majority of inmates — eventually get out, shouldn’t all efforts of the government be focused on changing lives to reduce repeat offenses? Isn’t that the best use of our tax dollars? Our whole system would have to change in a radical way — it would need to be far more therapeutic than punitive — to make any difference in the future. Ask yourself: What’s holding us back from that radical change? Fear? Racism? Bureaucratic lethargy? Public officials too unwilling or too nervous to take up the cause?

You could look at Warren’s record as a long series of failed opportunities to get convictions. I have a different view. I look at his first arrest for a violent crime — when he was 14 — and wonder why someone didn’t intervene, early and intensely, in Warren’s life to get him on a different track. At some point, there must have been an opportunity for a course correction. It’s too late now, and way too late for his victims.

Discover more from Dan Rodricks

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.