A castaway sailor and the shuttering of a great newspaper

Seventy years ago, the military dictatorship of Gustavo Rojas Pinilla of Colombia shut down one of the nation’s best newspapers, El Espectador, after an expose by a 28-year-old reporter who would go on to become one of the world’s most famous novelists.

It’s a story worth telling in the time of Trump should any American still believe such a thing could not happen here. It’s very clear to me, and to many of my fellow citizens, that Trump is trying to quash dissent in any form, that members of his regime will do anything to stifle opposition speech. Trump continues to treat the news media as “the enemy of the people” while pressuring media corporations, restricting press access and cutting funds for public broadcasting. Some of the corporate owners of news organizations have caved to Trump threats or made pre-emptive concessions to the regime. Many news organizations, however, continue to scrutinize what is likely the most corrupt administration in American history.

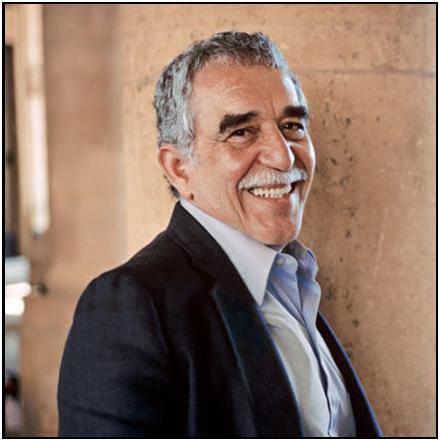

So today I’m indulging one of my favorite subjects — the life, as a young journalist, of the great novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez, known as Gabito to his family and Gabo to his friends and, ultimately, millions of people across Latin America and the world. His most famous work, the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, has been published in 37 languages, with more than 50 million copies sold.

It has one of the most famous opening lines in modern literature:

“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

One Hundred Years of Solitude is considered the first South American novel to gain international attention. For many people it was their first experience with what came to be known as the magical realism that animated Garcia Marquez’s stories, with words like so many amazing, colorful butterflies rising out of a jungle. It is a challenging read, but worth the long trip. (I always suggest Love In The Time of Cholera, or his short stories, for readers new to Garcia Marquez.)

One Hundred Years of Solitude brought Garcia Marquez fame and a fortune that seemed to him as remote as the fictional village of Macondo at the time that he wrote it. He was so poor that, when he finally finished writing One Hundred Years of Solitude, he could not afford postage for the full manuscript, so he mailed only half of it to his publisher in Buenos Aires; his editor sent him enough money for postage for the other half. One Hundred Years of Solitude, which was translated into English in 1970, paved the way for Garcia Marquez’s Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982, and it brought recognition to the new wave of Latin American writers.

In the 1970s, 80s and into the 90s, Garcia Marquez wrote several other novels and short stories, but among his work is also some non-fiction. In fact, for many years before the publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude, Garcia Marquez worked as a journalist in his native Colombia. While not as much of that considerable body of work has been published in English, there is a growing recognition of the value of that work and an interest in the road signs to Garcia Marquez’s life as a novelist that his reporting offers.

In 1981, he told the Paris Review: “In journalism just one fact that is false prejudices the entire work. In contrast, in fiction one single fact that is true gives legitimacy to the entire work. That’s the only difference, and it lies in the commitment of the writer. A novelist can do anything he wants so long as he makes people believe in it.”

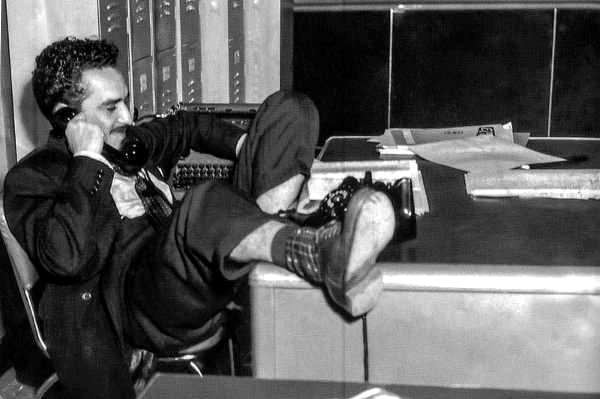

Garcia Marquez tells a lot about his life as a reporter in Colombia in his biography, Living To Tell the Tale. In fact, in the very beginning of that book, we find Gabo — tousled hair, untrimmed moustache, jeans, flowered shirts and sandals — with friends in a cafe in Bogota. He describes himself in 1950, after leaving his boyhood home in the river village of Aracataca, in Colombia’s Caribbean region, having turned against his parents’ wishes by dropping out of law school at the age of 24.

In nearby Barranquilla, Garcia Marquez became friends with other writers who worked as journalists but also had an interest in fiction and poetry. They studied authors in a bookstore and in a library; they discussed novels, and came under the spell of William Faulkner. During that time, Garcia Marquez worked for newspapers, El Universal and El Heraldo, and he contributed to a column called “La Jirafa,” or “The Giraffe,” and he signed his contributions, “Septimus.”

In 1954, García Márquez moved to another newspaper, El Espectador, where he became the country’s first newspaper film columnist; he also developed a reputation for well-written feature stories, and particularly for those that reconstructed events. So that’s what brings me to his breakout work, his big story.

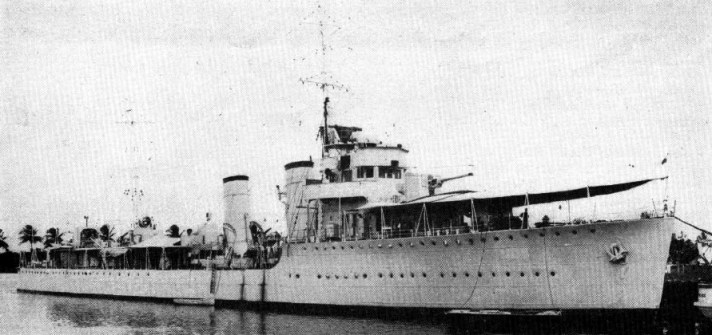

On February 28, 1955, eight members of the crew of a Colombian Navy destroyer, Caldas, fell into the Caribbean Sea. Although the Colombian government attributed the sinking to a storm, Garcia Marquez’s reporting turned up another cause.

The Caldas had been in the port of Mobile, Alabama for several months while it underwent repairs. It was to cross the Gulf of Mexico and traverse the Caribbean Sea and return to Cartagena, Colombia.

But about 200 miles from the port, the Caldas hit wind and waves and the eight sailors were tossed overboard. One of them, Luis Alejandro Velasco, managed to get to a life raft dropped by the destroyer.

Unable to reach them against the wind, his shipmates drowned a few yards from where Velasco was. While the ship continued its course, Velasco was adrift on the raft for 10 days, without food or water. Search planes could not find him. During the time Velasco was at sea, his family attended his funeral.

But the sailor survived. He survived wind, rain, scorching sun, shark attacks, fits of madness and a storm on the seventh day. He washed up on shore in Colombia.

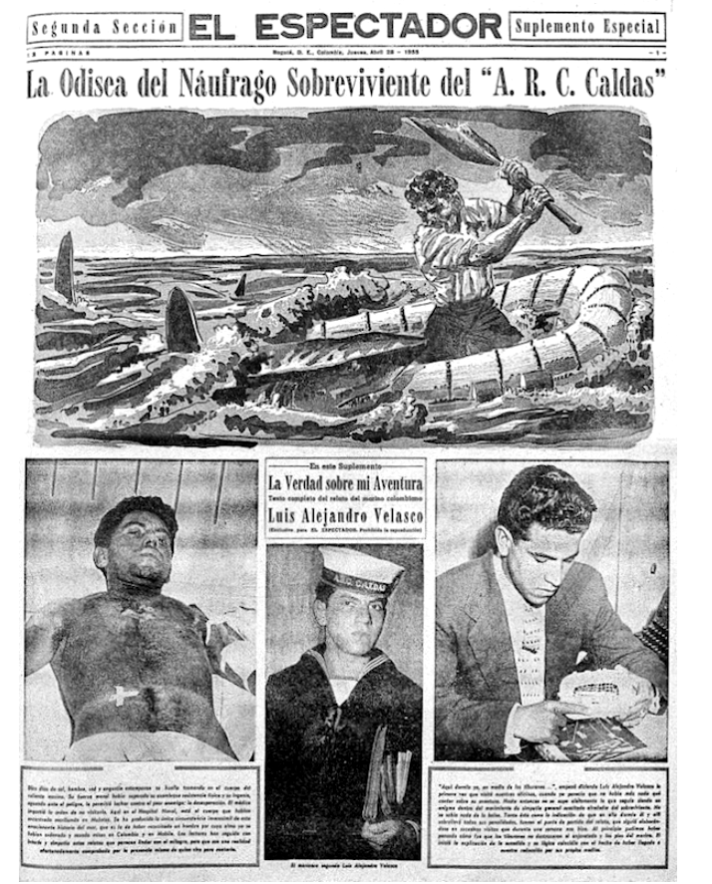

Garcia Marquez managed to get an interview with Velasco and it lasted 120 hours. He convinced his editors to let him write a series of stories in the sailor’s voice, what the journalist and author Miles Corwin called “a feat of modernist ventriloquism.”

The stories ran in installments in El Espectador over 14 days. People came to the newspaper each afternoon demanding to read the next installment.

In his reporting, Garcia Marquez uncovered something the government did not want the public to know — that the Caldas had been loaded with contraband appliances: television sets, refrigerators and stoves from the U.S. destined for the households of Colombia’s political and military leaders. It’s believed to have been one of the reasons sailors went overboard in the storm — the extra weight of the contraband had left the ship unbalanced, listing dangerously in rough seas.

The story became a scandal.

The Colombia Navy was not pleased.

The Rojas regime was not pleased, either.

By the time the series of stories ended, El Espectador’s circulation had almost doubled. The public always likes an exposé, but what made the stories so popular was not simply the explosive revelations of military incompetence and corruption. García Márquez had managed to transform Velasco’s account into a narrative so dramatic and compelling that readers lined up in front of the newspaper’s offices, waiting to buy copies.

After the series ran, the government denied that the destroyer had been loaded with contraband merchandise. But García Márquez tracked down crewmen who owned cameras and purchased their photographs from the voyage. In those photos, the illicit cargo, with factory labels, could be easily seen.

According to Miles Corwin: “The series marked a turning point in García Márquez’s life and writing career. The government was so incensed that the newspaper’s editors, who feared for their young reporter’s safety, sent Gabo to Paris as its foreign correspondent. A few months later the government shut El Espectador down. The disappearance of his meal ticket forced García Márquez into the role of an itinerant journalist who sold freelance stories to pay the bills — and, crucially, continued to write and develop his fiction.”

Raymond Williams, a professor of Latin American literature at the University of California, Riverside, who has written two books about Garcia Marquez, says that, in telling the tale of the sailor, “This is where Gabo’s gifted storytelling emerges.” Prior to the series, he suggests, García Márquez had been writing somewhat amateurish short stories. With Velasco, he was rising to the challenge of constructing a lengthy narrative: “The ability he has to maintain a level of suspense throughout is something that later became a powerful element of his novels.”

The Story of the Shipwrecked Sailor was published in Spain, and later translated into English. I recommend it as a very fine read. Also among Garcia Marquez’s non-fiction: News of a Kidnaping, published in 1996, about life in Colombia during the time of the Medellin drug cartel and Pablo Escobar.

El Espectador survived the 1955 shutdown by the Rojas government — and many other sanctions throughout its history. It is published daily, Colombia’s oldest nationally circulated newspaper.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez died at his home in Mexico City in 2014 at age 87.

One last thing about journalists who turn to fiction: Garcia Marquez was a fan of Ernest Hemingway’s work. Before he became a novelist, Hemingway had been a reporter for The Kansas City Star and a foreign correspondent for The Toronto Star. Hemingway and García Márquez also differed on how lasting one’s journalistic apprenticeship should be. The former admitted that journalism was good training for a young novelist, but contended that it was important to get out in time, because newspapers could ruin a writer. García Márquez felt otherwise. “That supposedly bad influence that journalism has on literature isn’t so certain,” he said. “First of all, because I don’t think anything destroys the writer, not even hunger. Secondly, because journalism helps you stay in touch with reality, which is essential for working in literature.”

Note: A lot of the details of the Caldas scandal came from excellent reporting by Miles Corwin, the Garcia Marquez biography that I mentioned, and numerous other sources that I used in preparation for a talk about the author at The Ivy Bookshop in Baltimore in 2017.

Discover more from Dan Rodricks

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.