I know exactly what I was doing on July 16, 1973, when Alexander Butterfield told the Senate Watergate Committee that all Oval Office conversations in the Nixon White House were recorded: Watching the hearing on television while getting dressed for the 4-to-midnight shift as a reporting intern for The Patriot Ledger in Quincy, Mass.

I had been following the Watergate hearings every weekday before heading to work. I was transfixed. Hour by hour, witness testimony seemed to bring the Watergate breakin and coverup closer to the president. Butterfield’s disclosure of the White House tapes pretty much doomed Nixon. A year and eight days later, the Supreme Court ruled 9-0 that the Watergate tapes had to be released to prosecutors and members of Congress. Facing impeachment, Nixon resigned three weeks later.

While his August 1974 farewell is a vivid memory, the summer of ‘73 provided the nation’s first raw insight into Nixon administration sleaze and, for me, big inspiration for the career in journalism on which I had just embarked.

Remember: The Watergate scandal unfolded first in the pages of The Washington Post and the New York Times in 1972. It was newspaper reporting that revealed details of the Watergate burglars and the various money trails that led to the Committee to Re-elect the President.

So, the timing of my summer internship at The Ledger, a widely respected evening daily in the Boston suburbs, could not have been better. A rising college sophomore with an interest in newspaper work had just been given a great opportunity.

It was the late Ed Querzoli, managing editor of the paper, who took a chance on me. I had not even finished my freshman year at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut when he invited me to his home in Bridgewater, Massachusetts for an interview. Ed and his wife had 13 children, and while I waited to speak with him at his dining room table, I noted seven lunch boxes lined up on the kitchen counter, presumably for the next school day. I don’t remember much from the interview except that Ed seemed to be a genuinely nice man, remarkably composed for a father of 13. Even more remarkable: He appeared to be open to giving me an internship as a news reporter.

He called me at school a week later to say I could start that June, and The Ledger would pay me $100 a week.

That made me both happy and panic stricken.

I had only graduated from high school a year earlier. My main interest had been sportswriting; I was still learning how to write a news story. I typed with three fingers. I owned only two neckties and one cheap polyester sport coat. I did not own a car.

But the summer of ‘73 was in all ways great, and not just because my parents helped me buy my first car, a used Ford Galaxie 500.

Ed Querzoli and his staff of editors threw me right into the daily news operation. It was a whirlwind.

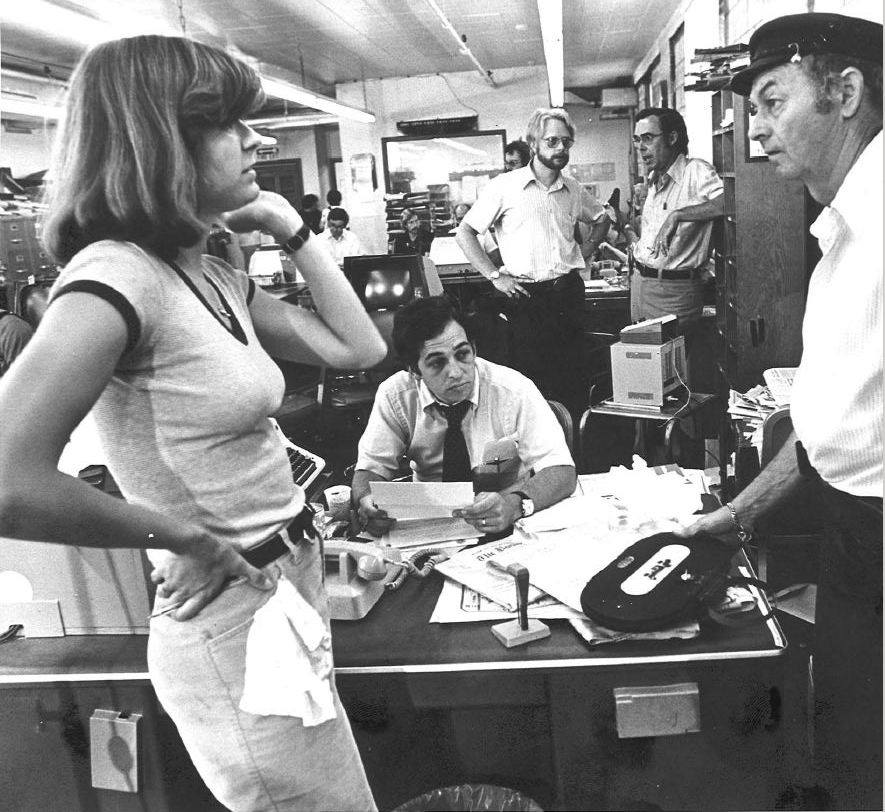

The long newsroom, three stories above Temple Street in Quincy Center, had large windows, rows of gray steel desks with manual typewriters and rotary phones and stacks of telephone books and newspapers. There were areas designated for different sections of the newspaper — sports, arts and culture, society and home, photography and editorial. The top editor, the aloof Donald Wilder, ruled from a large office behind the city desk and the copy desk. The news editor, Dick Carlisle, wore white shirts and dark ties every day; he was pleasant but all business, insisting on accuracy in all phases of news writing. He hated — I’m using the word hate here — when a reporter got something wrong, requiring a published correction. He believed the accuracy and completeness of obituaries served as the threshold to the Ledger’s credibility. It was Dick Carlisle who, with quiet terror, first instilled in me the fear of consequences from incorrectly spelling someone’s name.

The editors assigned me a different task every day. I telephoned fire and police departments in each town on the South Shore to gather and compose accounts of their overnight runs. I wrote obituaries, sometimes five per shift. I covered car accidents and fires. I once covered a lottery drawing and wrote a feature about a blind minister. I went to the State House in Boston a few times to cover hearings. On weeknights, I covered meetings of zoning boards, planning committees, school committees, boards of selectmen — and hustled back to Quincy to write my stories before midnight. One time, Kingston officials debated raising the town’s clam-digging license fee before tabling the matter, meaning there was no decision and leaving me to sort out news from nonsense in four hours of testimony.

My copy was rough. I would hand a story to Paul Mindus, an older reporter and the sharpest stylist on staff, for his suggestions. He was a great help. I think my copy slowly improved over the summer. An overnight editor, Clive Davies, was a big help, too. He was a wise guy, but a careful editor and saw that I really wanted to get good at writing a news story, no matter how dull the subject.

Almost every adult in the room — seasoned reporters who typed hard and fast, smoked cigarettes, gossiped and talked politics, and burned up the telephone lines — took an interest in me, gave me advice. I think of Ray McEachern, Millie Potter, Sue Scheible, Maurice Riordan, Dick Kent, Jeff Grossman, Pat Desmond, Diane Baltozer, Bob Flavell, Mark Sweeney, Bob Sears, Marilyn Jackson, Jean Demos, Carl Beck, Jack Keough. There were others, so many good people.

Fred Turner, an assistant editor on the evening shift, pressed a heavy pencil on my first news story — about a fire at a piano company — ripped it to shreds, then rebuilt it in minutes, right before my eyes. “Here, take a look,” he said, handing a marked-up copy of the story to me so I could see what he had done. Fred had taken a know-nothing intern’s fractured account of a fire and turned it into a smooth read, fit for the Ledger’s front page. I learned more about organizing and writing a clean news story from that one experience with Fred than I’d learned in several hours of journalism classes.

The city room of the Ledger was always busy, almost always noisy, always collegial if not cordial. I was awed by the breadth of subjects that came up in conversations with editors and senior reporters. I was intrigued, entertained, inspired, mentored, awed and enlightened by the people who worked there. They each enhanced my knowledge of the world in some way or expanded my perspective on all kinds of issues facing American society. They read books and talked about them. They demonstrated a rich understanding of history, culture and the arts, of sports and science and health, of politics and law and business. They all seemed to know something about almost everything or everything about something. They were interested in the progress of society, in solving problems, in seeing that the government responds to the needs of people. They were vigilant and skeptical, and usually on the side of the underdog. They made me want to be a journalist.

Toward the end of summer, as the Watergate investigations played out, I covered a zoning board hearing in the town of Hingham. A company that already owned and operated several nursing homes in the Boston suburbs wanted to build another. A nurse and Hingham resident named Mildred Westover stood to tell the board it needed to examine the company’s track record in health care. It was deplorable, she said.

I approached her after the meeting to hear more, and what she told me led to the Ledger launching an investigation of the company. I did a lot of leg work on the story during the day, plunging into the commonwealth’s extensive inspection records of the company’s nursing homes. Westover was right; the company had been cited numerous times for violations of health standards. One patient had leaned against a soda machine and died, undetected by the staff for several hours.

Paul Mindus jumped into the investigation and took over. My summer ended and I went back to college, leaving all my notes with Paul. He finished the stories on the nursing homes, exposing their poor conditions, and the Ledger ran them on the front page with our shared byline. Paul’s later work and a state investigation led to charges of fraud against the company’s owners; they eventually applied for bankruptcy and their 27 nursing homes changed hands. It wasn’t Watergate but I felt we had served good public service, and the experience set me on a course rich in rewards ever since.

Discover more from Dan Rodricks

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Marvelous story, Dan. Glad someone with the name of Davies was one of your mentors too. Didn’t know you went to Bridgeport. I have an ex-son-in-law who did too. Good school!

Thomas Davies

South Yarmouth, MA

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dan: You are justifiably proud of your long career in journalism.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was indeed a wonderful time to be young and at the old Ledger. Spectacular memories. Thanks.

Pat Desmond, retired publisher Milton Times

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great piece. Thank you for mentioning my father and bringing back so many memories. All of us kids were raised on the Ledger, the news and stories of all you reporters fighting the good fight. Much appreciation for putting a smile on our faces, Dan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Martin. Your father was a great man. The people who worked for him loved him.

LikeLike

And boy did he loved you people, Dan. More than half of my siblings ended up writing for a paper or broadcast news outlet at some point, inspired by stories of you folks. Keep on keeping on: your more important than ever.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ugh. A typo (your). Any good proofreaders out there : )

LikeLike

Dan, what great reminiscences! It was certainly a different time in journalism, and I’m glad to see/read your writings. Spot on! Thank you. Marilyn Jackson

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the memories, Dan. I remember you well. Glad you mentioned Ed Querzoli. He hired me, too, and I never left journalism. He was a real newspaperman and gentleman. All those you mentioned were true journalists. To this day, I’m proud to have worked with each of them – and you.

LikeLiked by 1 person